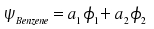

Thanks to the double slit experiment, we already know one of the principles of quantum mechanics, namely that we are able to calculate the correct probability amplitudes for a system by describing this system as a set of partial amplitudes weighted by coefficients. We now want to consider a system with only two states which will be helpful to explain many phenomena in chemistry and spectroscopy. We imagine benzene with the following pair of electronic structures.

| Benzene = |  |

|

Although we do not know either the amplitudes |1> and |2> of benzene in these two electronic configurations or the respective energies, we pretend we have both and incorporate one principle: Due to symmetry, both configurations have identical energies which will be denoted as Eo. Another assumption we can make is that the coefficients a1 and a2 are the same, but we have to be aware that the probability density is proportional to the square of ψ. Thus, the sign of the coefficients remains questionable and, at best, we are able to state |a1|=|a2|. But additional mathematical principles pave the way to a solution.

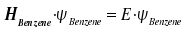

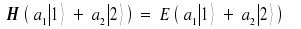

For a start, although the Hamilton operator H is undetermined, we have Schrödinger's equation for benzene.

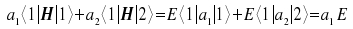

Within this equation, the wave function ΨBenzene is replaced by the linear combination introduced above.

We multiply the equation with <1| and with <2| and apply the

distributive law. As we know the states <1| and <2| to be

orthonormal, the respective values of one and zero for the terms

<1|1> = 1 and

| Multiplied with <1| : |  |

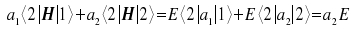

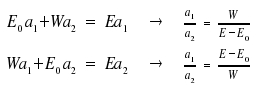

| Multiplied with <2| : |  |

By combining both equations, we eliminate the fraction a1/a2 and find the energy states EI and EII.

We draw the conclusion that there are two stable states, one of them with magnitude W below, the other of magnitude W above E0. Usually, EI is the energy of lower, EII the energy of the higher state (a convention that would favour reversing the ± sign, but we won't care for that here). In case |1> and |2> do not at all interfere with each other, EI , EII and Eo are all the same.

Instead of W, we now write -ΔE. For the energies of the two stationary states |I> and |II> we then recieve

At last, we want to characterize the shape of the electronic configurations |I> and |II>. Therefore, we insert the solutions for E into the expression found for a1/a2 derived above. This establishes a1 = ±a2 as mathematical link between the two coefficients, a relation already expected due to general considerations. If we finally introduce the conditions <I|I> = 1, and <II|II> = 1, i.e. normalize the established linear combinations, we get

All these considerations hold true not only for benzene but also for ammonia. Energy diagrams and an interesting application have been presented in the respective unit. The background to this treatment is that molecule is able to switch between two possible states:

| |NH3> | |1> | |2> | |

|

|

||

| N atom | above | below | the plane the three Hydrogen atoms |

Benzene has higher interaction energy since light electron can move quite fast between two possible benzene configurations. In contrast, an atom is a massive particle. Thus, the tendency for the nitrogen atom to change position and the interaction energy ΔE is found to be much smaller. The electronic transition of Benzene is reflected by absorption of ultraviolet light whereas the molecular rearrangement within the ammonia is reflected by a peak within the infrared region.

In the next unit, we are going to use the same approach to analyze the cationic H2+ molecule and to molecular hydrogen.

![]()

Auf diesem Webangebot gilt die Datenschutzerklärung der TU Braunschweig mit Ausnahme der Abschnitte VI, VII und VIII.